Closures

Closures are a very important part of JavaScript and are often misunderstood. Using Chrome DevTools can show you what is happening within a function, which may help you understand the process.

I think the best description of closure is from Kyle Simpson:

Closure is when a function is able to remember and access its lexical scope even when that function is executing outside its lexical scope.

Another description, from the Mozilla Developer Network:

A closure is the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared.

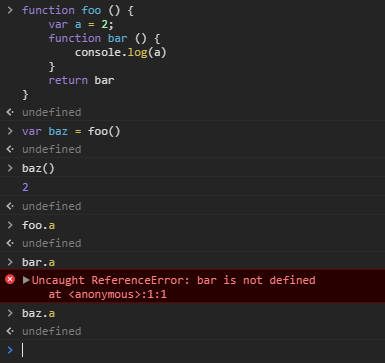

So to demonstrate this:

As you can see variable a can’t be referenced, yet it still exists when we call baz() - the Garbage Collection process hasn’t removed the variable as a reference to it still exists, in the bar function.

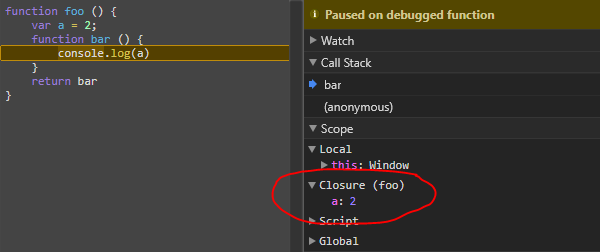

And with DevTools we can see this in action. First, we want to create a breakpoint when calling baz - in the console use command

debug(baz)

baz()

This will invoke the debugger, automatically stopping on the first executable statement (the console.log statement).

In the code panel, you can see we’ve stopped in function bar, which not only still exists but references the variable a. And in the Debugging pane under Scope, you can see the debugger actually shows us the closure on variable a.

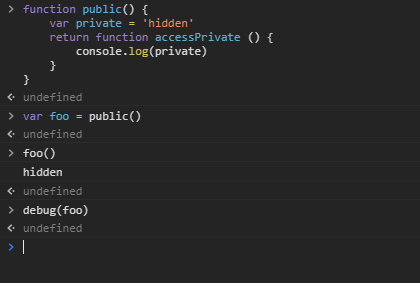

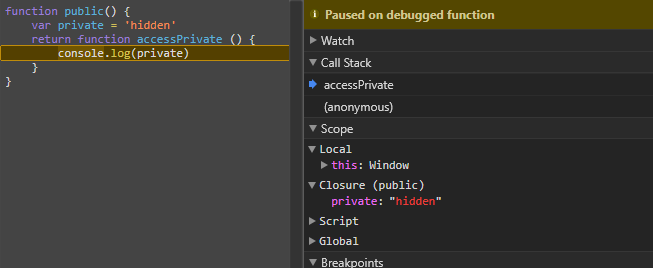

Private variables

Closures allow us to create private variables that cannot be accessed from outside a function:

again this will let us see what closure is in-scope

The classic example for loop

The most common demonstration of (lack of) closure is the for-loop

function foo() {

for (var i = 1; i <=5; i++) {

setTimeout(function loop() {

console.log(i)

}, i*1000)

}

}

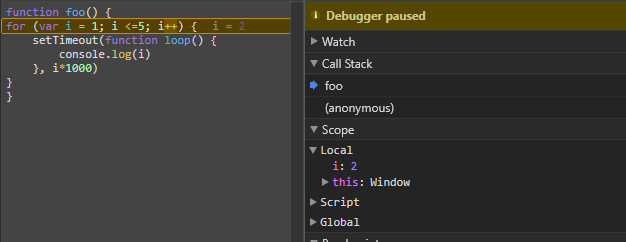

which will return ‘6’ five times. To see why we can use the debugger again, and step through the function:

After several iterations you can see i is now 2, but looking at the scope you can see no closure in the i variable, each loop isn’t keeping its own copy of i. As a result of this when setTimeout finally triggers it only has access to the value of i after the for loop completes (which will be 6 as i<=5 will return false at this point).

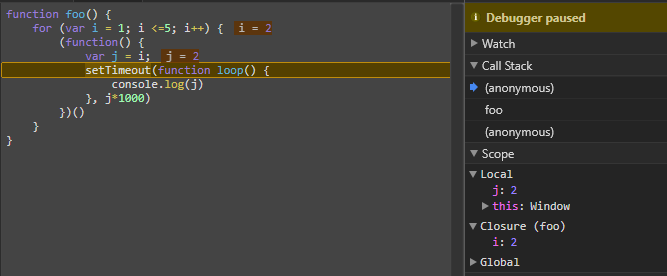

Changing foo to use an IIFE, with its own variable:

function foo() {

for (var i = 1; i <=5; i++) {

(function() {

var j = i;

setTimeout(function loop() {

console.log(j)

}, j*1000)

})()

}

}

Gives each iteration it’s own copy of i, as can be seen from the Closure in scope.

This function then returns the expected 1,2,3,4,5 output.

Let variable

A simpler solution to the above is to use the let keyword - when used in a for-loop the let will be declared for each iteration, so just changing the original for-loop to use let i instead will give us the 1,2,3,4,5 output we are after:

function foo() {

for (let i = 1; i <=5; i++) {

setTimeout(function loop() {

console.log(i)

}, i*1000)

}

}

More Info

For more info see Kyle Simpson’s Scope & Closures book

or the MDN article on closures